[ad_1]

Last month, Ravi and Neha Handa, along with their son, spent over a week in Singapore on their Diwali vacation. The family stayed in swanky hotels, one of them especially known for its underwater bedrooms overlooking 40,000 marine creatures. It was not the first of such holidays. For the couple, money woes flew out of the window in 2022, when they retired with a fat corpus. Today, they have approximately ₹15 crore invested in real estate, mutual funds, stocks, cryptocurrency, national pension scheme (NPS), personal provident fund, and sovereign gold bonds.

In March 2021, Ravi sold his startup ‘Handa ka Funda’, a CAT and MBA e-learning site, which he founded in 2013, to the edtech company Unacademy for an undisclosed amount. This allowed the two, then in their late 30s, to achieve financial independence and retire early (FIRE) in 2022.

Among Indians, there is a rapidly growing interest in FIRE. Many wish to exit the workforce to gain early financial freedom and control over their life choices. Ravi, now 42, has achieved that.

What is FIRE? Lavanya Mohan explains

| Video Credit:

Thamodharan B.

The FIRE movement has been grabbing headlines and social media interest this year. In India, the conversation is picking up pace, with several podcasts and video interviews on the topic. The sub-Reddit FIRE_Ind has nearly 65,000 members and around 46,000 weekly visitors. Here, one can share anecdotes about their journey towards financial independence and seek advice from ‘FIREd’ individuals such as Ravi. But experts say ground realities are starkly different from online projections. As the year nears its end, we take stock of the situation: young India is eager to FIRE, but can they afford to do so?

Ravi and Neha Handa

A western import

Lavanya Mohan, chartered accountant and author of Money Doesn’t Grow on Trees (2025), a personal finance guide, explains the idea migrated across the ocean. “[FIRE] is a cultural movement in the West, especially among millennials who lived through the 2008 crash and watched job security evaporate. For many of them, the goal wasn’t to stop working, it was to stop depending on work. The concept spread from Silicon Valley engineers and personal finance blogs to everyday professionals who wanted ‘time freedom’ and [a release from] the rat race,” she says.

Illustration by Arivarasu M.

A 2024 nationwide survey from Grant Thornton Bharat LLP titled ‘India’s pension landscape: A study on retirement reality and readiness’ found a growing desire among young Indians for early retirement: 43% in the under-25 group studied hoped to retire before the age of 55. The age group prioritised work-life balance and leisure over extended career spans.

FIRE, however, is vastly different from Voluntary Retirement Scheme (VRS). “VRS happens when your employer offers you a package to leave early — it’s reactive. FIRE is proactive — something you architect for yourself, often years in advance, through saving and investing aggressively,” adds Mohan. “One is born out of redundancy; the other out of design.”

Save, invest, live (frugally), repeat

To achieve FIRE, the first tip offered is obvious: live below your means. Mumbai-based mechanical engineer James Fernandes has been living a “frugal” life since COVID-19. The pandemic-triggered spike in health expenses and job-market insecurities made him reconsider his priorities. He implemented a strict saving and investing routine: no online shopping, no eating out, limited social outings, and swapping trains for flights. “Budgeting is important. It doesn’t mean not spending at all but knowing what one spends on,” says the 41-year-old, who hopes to retire in the next four years.

James Fernandes

For Noida-based Jayant Kumar, 45, “the priority was always to invest before spending”. Kumar managed to reach his FIRE number — 35 times his annual expenses, with separate buckets for children’s education and marriage — by the end of 2023 and quit working full-time in October 2024. He says, “I started investing aggressively in 2015 and by 2020, I was saving more than 60% of my income. Compounding did a great job of adding wealth to my investments.” The former IT professional, whose focus now is family and health, adds, “Saving small amounts might seem insignificant, but can yield multifold returns in the long run. Even with rent and EMIs, one should save 10%-20% of their salary consistently.”

Jayant Kumar.

As the idea travelled continents, FIRE aspirants have been chasing borrowed numbers and percentages, which experts say spread more misinformation. According to Google search results, to achieve FIRE, one must save and invest aggressively — often 50%-75% of their income — to build a corpus that is roughly 25 times their annual expenses. This enables them to maintain a safe withdrawal rate of 4% post-retirement. Does this apply to Indian realities? “Those figures come from the U.S., where inflation hovers around 2%-3% and markets behave differently. In India, the maths is far less forgiving,” explains Chennai-based Mohan. “Inflation is higher, returns are volatile, and family obligations rarely shrink with age. Saving 75% of your income is hard enough in California. In Indian metro cities, it’s near-impossible.” One should also be wary of the famous “4% rule”, she warns. “It collapses when your post-retirement medical and lifestyle costs grow faster than your investments.”

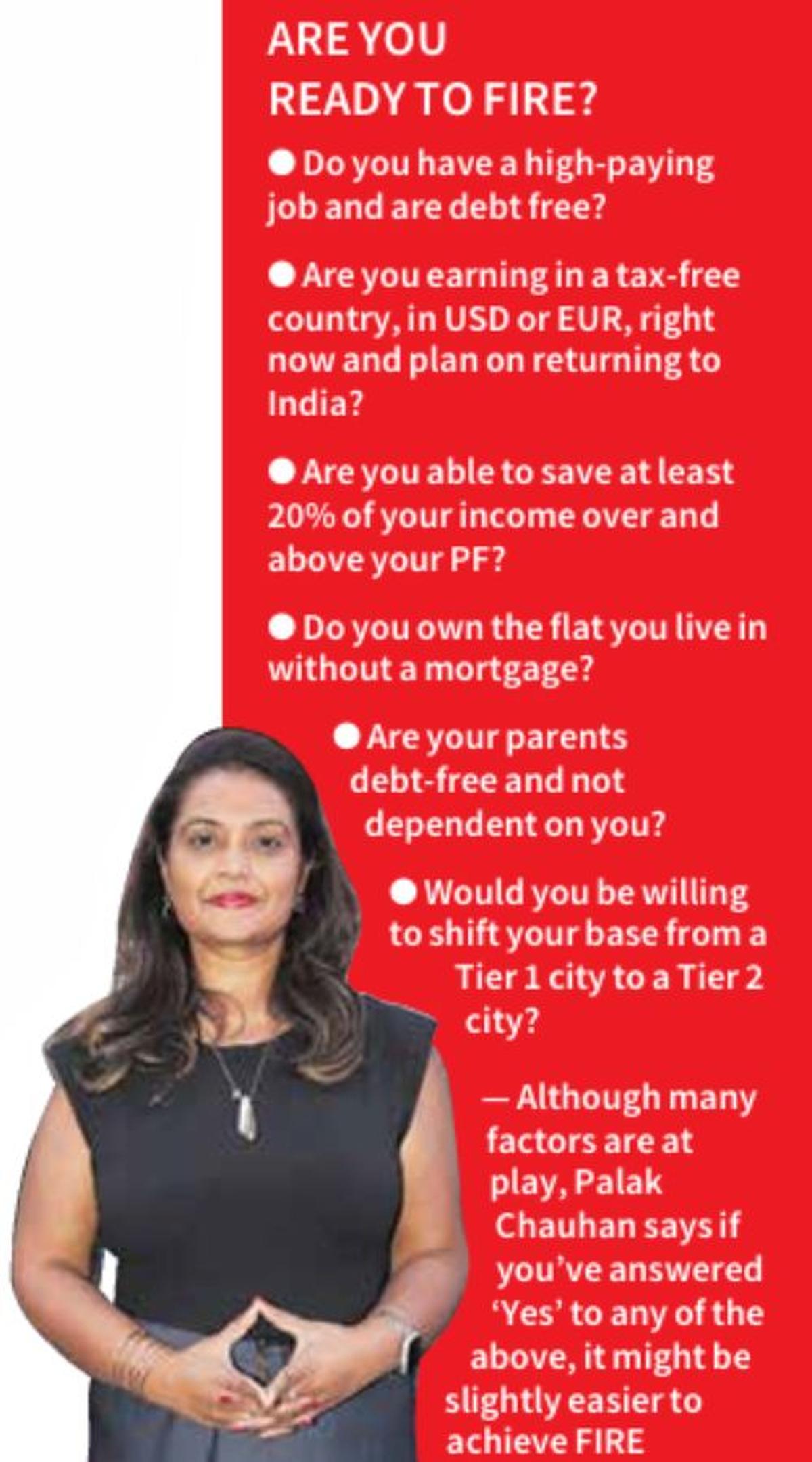

Pensions actuary Palak Chauhan, Fellow of the Institute of Actuaries of India, who has worked as a global employee benefits advisor for Nestlé, Citigroup, General Motors and General Electric, says it doesn’t add up in the Indian context. “People think personal finance is as simple as putting everything in a formula. It’s not. One needs to consider assumptions that are relevant to each economy. And 25 times of one’s annual expenses is irrelevant to India. A more realistic estimate of the right expense number comes to around 30-33 times.”

She goes a step further to add that in a country as vast as India, there are too many variables at play that make it very difficult to zero in on a particular percentage; numbers floating online aren’t etched in stone. Monika Halan, personal finance expert and author of Let’s Talk Money: You’ve Worked Hard for It, Now Make It Work for You (2018), says each life is different. “You need to take professional help to do retirement planning.”

Monika Halan, personal finance expert and author.

““Young people want shortcuts to make a lot of money quickly. In my experience, this is a sure way to lose a lot of money and peace of mind.””Monika HalanPersonal finance expert and author of Let’s Talk Money

A pipe dream?

Mohan offers a grounded perspective. “FIRE assumes you can save half or more of your income. That’s a luxury when you’re juggling EMIs, caregiving, and inflation that won’t quit. DINK (double income, no kids) couples and high-income professionals may manage it, but for most middle-class Indians, the real dream is to retire with dignity, not early,” she says.

For Mumbai-based customer-service employee Eeshan (name changed on request), 28, saving 75% is far-fetched when making ends meet is a priority. “Living alone on rent, managing all expenses without any financial support, makes the idea of early retirement feel impossible,” he says. “After paying rent, EMIs, bills, and other necessary expenses, I make it a point to set aside a small amount each month — I can manage 5% in SIPs. With the expenses ever increasing and salaries not matching them, it seems impossible to get out of this cycle,” he adds. It, thus, appears that only a certain section can afford to achieve FIRE — the high-net-worth individuals (HNIs) and ultra-HNIs.

Money makes money

Vivek Kaul, finance columnist and author of Bad Money: Inside the NPA Mess and How It Threatens the Indian Banking System (2020), says, “Only when one invests a lot of money, and catches the upcycle [like some people have managed to do in the last five years in the stock market], does the concept of FIRE work. Invested money grows and leaves one with more money to retire early. This is an important point that people tend to forget.”

Vivek Kaul, finance commentator and author.

What captures the imagination of FIRE enthusiasts are the success stories. FIRE allows Ravi to go on extended foreign trips with his family, often impromptu. “We look at our expenses after the trip instead of planning the budget,” the IIT Kharagpur alumnus says. “Earlier, duration, airlines and seats, mode of transport, accommodation, neighbourhoods, and places to eat would be budgeted. Now, we plan based on comfort.” In Singapore, he splurged on Express passes at Universal Studios, which cost him around $300 (approx. ₹20,397) for his family of three. Before FIRE, he would have opted to stand in long queues in the sweltering heat instead.

Paradox of leisure

Psychologist Dhara Ghuntla, affiliated with Mumbai’s Sujay Hospital, warns that early retirement experiences might not be the same for everyone. “Early retirement is often imagined as freedom from pressure, but it can also mean freedom from structure, stimulation, and meaning — the three pillars that sustain emotional and cognitive health.” The situation might be even worse for a social butterfly. “Occupational environments provide built-in opportunities for social regulation — interaction, feedback loops, and a sense of contribution. These play a protective role against social withdrawal and emotional dysregulation. When work is abruptly removed, especially without alternative social roles, one might face increased isolation, loss of social confidence, and emotional blunting,” says Ghuntla.

A children’s edutainment workshop organised by Neha Handa.

The loss of a professional identity post-FIRE is why Ravi is building an AI-driven personal-finance platform for Indians. “I’m calling it Handa Uncle — the identity crisis is obvious.” With the monetary cushion to experiment, he adds that there is also a vanity factor attached to it. “Who knows, because of [Handa Uncle], someday I might be on the cover of Forbes magazine.”

His wife, Neha, 41, prioritises motherhood now. She drops off and picks up their four-year-old from school and organises weekend edutainment workshops (by choice, not necessity) in their housing society in Jaipur. “There’s play, arts and crafts, storytelling, and other brain gym activities,” she says.

Dr Ruksheda Syeda, psychiatrist and psychotherapist at Trellis Family Centre, Mumbai. (Special arrangement)

It appears that an ingrained hustle culture in Indians is another reason why leisure can’t be enjoyed, despite working hard towards an early retirement. Dr Ruksheda Syeda, psychiatrist and psychotherapist at Trellis Family Centre, Mumbai, says, “Indian systems of family, education, social structures, and gender roles are constructed in response to the pursuit of achievements as a mark of success, class, identity and self worth. The fear of losing to competition encourages the constant grind and engagement [in work].” The former President Bombay Psychiatric Society says that a discouragement to explore passions outside of academic excellence and work achievements is also to blame. “Interests, extra curricular activities, and hobbies outside of academics and professions aren’t given as much importance. Post retirement, what can a person enjoy while remaining productive, entertained and cognitively sharp when one hasn’t explored and developed a curiosity in younger days?”

A word from the sceptics

Meanwhile, financial experts advise caution when it comes to online posts about success stories. “FIRE is basically selling a story — by those in the business of managing money,” says Kaul. “They need a catchy story to sell to their prospective clients. The moment one uses a term like FIRE, it grabs the attention of people who are financially illiterate or not as literate to be able to see through the fact that it is mere storytelling. It is important to look beyond what is being projected as a story on social media.”

Halan agrees. “FIRE is a dream sold by influencers who display their lifestyles to others and encourage them to either take more risks with their money or do some side hustle to make more money than a job pays,” she says. “But it does take a good 20-25 years to get there [to FIRE] on a salary.”

Regardless of FIRE, savings are advised as important for working and non-working individuals. Kaul says, “The first aim should be to save money and build an emergency fund, and then go about building more savings.” While he acknowledges that people typically tend to save for a particular goal, he says one should aim to save in order to make better decisions for themselves “and to have some control over your time”. “Say, you’re faced with sudden unemployment but have money in the bank, this means that you have slightly more time to look for a new job instead of settling for whatever comes your way,” he adds.

Go easy, not aggressive

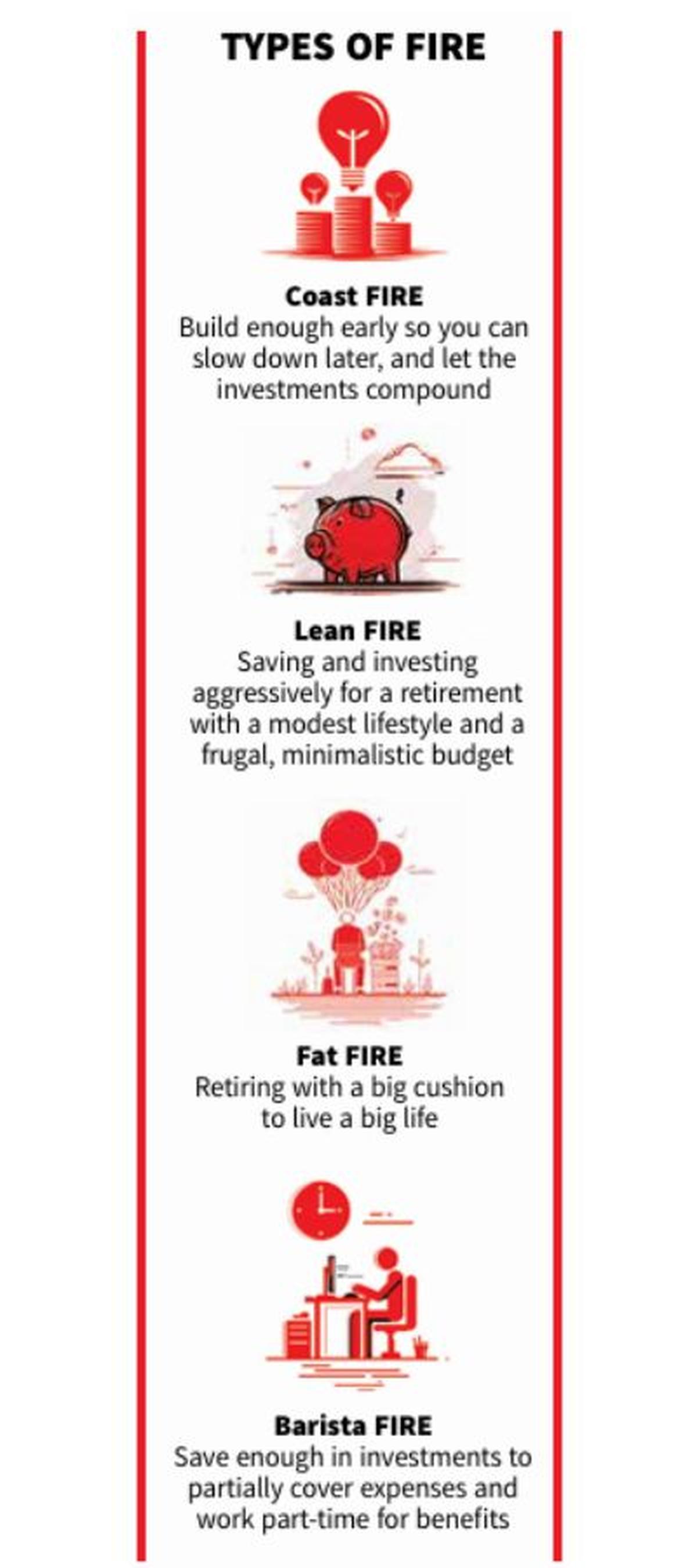

Instead of running behind numbers off the Internet to save aggressively beyond your means, Mohan suggests going easy on hard-core FIRE and to opt for Coast FIRE or Barista FIRE, which feel “more humane”.

“The point isn’t to retire at 35 with a big corpus. It’s to reach a stage where money doesn’t dictate every decision,” says Mohan. “FIRE is not about never working again. It’s about optionality and never feeling trapped again. You can work fewer hours, freelance, consult, teach, run a business, or do something completely different.”

Luck by chance

FIRE might seem like an exit strategy from an all-consuming 9-to-5 rat race, but the path to financial independence is fraught with risks and requires the correct alignment of many factors. “There’s so much competition in India, hard work and talent are not enough — one needs luck [and privilege] by their side,” says Ravi. “Someone can keep saving and do all the right things, but they can still end up in an unfortunate situation.”

The author is a Bengaluru-based features writer.

[ad_2]

Indians on FIRE | Retire early: When aspirations meet reality, or do they?