[ad_1]

The story so far: About 500 Indian citizens who recently fled the KK Park cyber crime hub in Myawaddy township, near the Thailand border in south-eastern Myanmar, are set to be repatriated by the Indian government. This incident, along with numerous similar cases, highlights how the global scam centre crisis has reached alarming proportions in Southeast Asia.

What is KK Park?

KK Park is one of the most notorious “scam cities” on the Myanmar-Thailand border — a massive, purpose-built compound in the Myawaddy township in Karen State, controlled by a junta-allied Border Guard Force (BGF) led by warlord Saw Chit Thu, who has close personal ties to Myanmar’s junta chief, Min Aung Hlaing. The U.S. Treasury sanctioned Saw Chit Thu earlier this year for his deep involvement in criminal operations, citing forced labour and links to the scam compounds.

Following reports of widespread Starlink usage at these compounds, the Myanmar junta conducted a “raid” into the KK Park compound and confiscated 30 Starlink devices. However, The Irrawaddy reported that democracy activists described the “raid” as a staged public relations stunt. According to sources cited by the outlet, senior criminal staff were warned to move from the area, and the BGF began transporting Chinese nationals out of KK Park as early as the evening before the raid. This media-friendly operation coincided with a U.S. Congressional investigation into the use of Starlink at scam hubs, besides U.S. President Donald Trump’s attendance at the ASEAN summit in Malaysia last week. The “raid” did cause panic, enabling thousands of low-level workers to flee. The Irrawaddy reported that thousands queued at border gates hoping to cross into Thailand, with locals saying BGF had coordinated with the regime on the operation.

What is the scam centre business model?

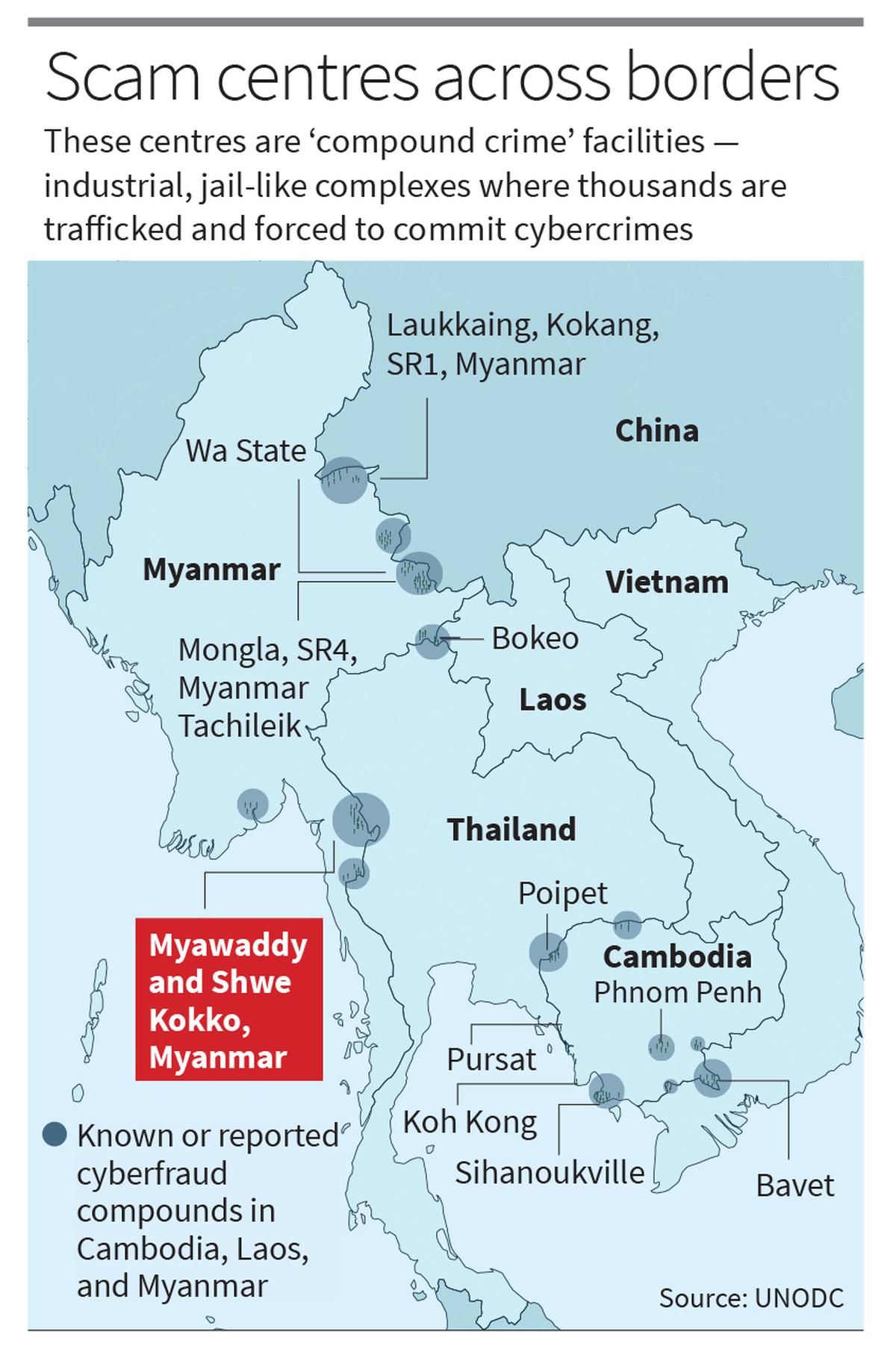

The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) calls these “compound crime” facilities industrial, jail-like complexes where thousands are trafficked and forced to commit cybercrimes. Traffickers post fake job advertisements for high-paying IT and marketing roles. Victims from India, China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Africa, and Latin America are flown to regional hubs like Bangkok, then trafficked overland and forced across borders into Myanmar or Cambodia. Once inside compounds secured by high walls and armed guards, victims’ passports are confiscated. They’re told they’ve been “sold” and must work to pay off their “debt,” enduring 12-hour workdays running online scams. Those who refuse face torture — beatings, electric shocks, starvation, and solitary confinement.

One of the most infamous scams run by such compounds is “pig butchering” (shā zhū pán), a combined investment and romance scam. Scammers build trust over many days, often faking romantic relationships, then convince victims to invest in fraudulent cryptocurrency platforms. After showing fake initial profits and luring larger investments, they “butcher” victims by disappearing with everything. Other scams include impersonation (posing as police or bank agents) and extortion through blackmail. While initially targeting Chinese citizens, victims now span over 110 countries across the U.S., Europe, and Asia, including India. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates these scams generate billions of dollars annually.

What role has Myanmar played?

The UNODC states that “industrial scale cyber-enabled fraud and scam centres… have converged [in] inaccessible and autonomous non-state armed group-controlled territories, Special Economic Zones (SEZs), and other vulnerable border areas.” Myanmar exemplifies this, with the GI-TOC identifying a profound lack of rule of law enabling “failed state” conditions.

In the mid-2000s, Myanmar’s military implemented the Border Guard Force scheme, allowing ethnic militias in Kokang (on the Chinese border) and Karen State (on the Thai border) to retain arms and autonomy in exchange for alliance with the junta. Junta chief Min Aung Hlaing, who led the 2021 coup, created this system and has been photographed conferring ranks on BGF leaders, including Saw Chit Thu, who are known scam kingpins. The 2021 coup and civil war gave BGF partners carte blanche to expand illicit empires that could be “taxed” to fund the junta’s war.

Moreover, Chinese citizens were the primary victims until 2024, making this a domestic political issue. The 2023 film No More Bets and the trafficking of Chinese actor Wang Xing amplified public attention. Frustrated by the junta’s inaction, China gave tacit support to Operation 1027 in late 2023 — a massive offensive by the “Three Brotherhood Alliance” of ethnic armed groups against the junta to close BGF-run centres. The operation caused major territorial losses for the junta in Shan State, and Myanmar handed over 41,000 criminal suspects to China by the end of the year. However, the crackdown merely displaced operations south toward the Thai border (and to Mandalay and Yangon), with scammers pivoting from Chinese victims to other nationalities.

Which other countries host these centres?

Cambodia is a major hub, with large-scale centres in Sihanoukville, Bavet, and O’Smach, mostly in repurposed casinos or “special economic zones.” The UNODC, Bloomberg, and blockchain firm Elliptic identify Cambodia’s Huione Group as a “critical node” and the “world’s largest criminal marketplace” financially enabling these operations. Through its “Huione Guarantee” subsidiary on Telegram, it allowed scammers to sell stolen data, malicious software, and money laundering services, and advertised “detention equipment” like electric batons for torturing workers. While Huione Pay is the “legitimate” public arm, U.S. sources told Bloomberg the company ran “Huione International Pay,” brokering deals between scammers and money “mules.” Elliptic identified over $91 billion in cryptocurrency received by Huione-linked entities in five years. Despite U.S. Treasury blacklisting in May 2025 and Telegram channel shutdowns, Huione adapted by rebranding, launching its own “USDH” stablecoin, and acquiring stakes in other criminal marketplaces.

How have Indians been affected?

India faces dual impacts — as a source of trafficking victims and as a target demographic. The Indian Air Force airlifted 283 citizens in March 2025 from Thailand who had been lured with fake job offers. The Indian Embassy in Myanmar reported over 1,600 nationals repatriated from scam hubs since July 2022. The 500 who fled KK Park are part of this pattern.

External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar stated, “We share the concern about cyber scam centres in the region which has also entrapped our nationals.” Indians have become a key demographic for pig butchering and impersonation frauds, making this both a consular crisis and a domestic security concern.

Published – November 02, 2025 03:07 am IST

[ad_2]

How do scam hubs in Southeast Asia operate? | Explained